Illustration in Preaching

The proper use of illustrations in preaching is in need of syntheses, syntheses, plural, because there are many divergent views as to the various facets of the proper use of illustrations in preaching. There are preachers who have extreme dependence on illustrations in their sermons. Some of these preachers sermonize their illustrations. (C. Roy Angell did this so effectively that he built his career on it.) Other preachers bombard their congregations with a series of illustrative stories at the expense of biblical exposition. These preachers represent one extreme. Partly in reaction to the overuse of illustrations, some preachers seek to avoid any use of illustrative material in their sermons. Other preachers feel, perhaps justifiably so, that they are not gifted in the communicating of an illustration in their sermons, so they use no illustrations. There is something to be said for and against each of these extreme positions. Clearly, a synthesis is needed.

A synthesis is needed, too, in the proper use of the various kinds of illustrations. Should most or many of our sermon illustrations be of a personal nature? Some preachers use themselves as a vehicle to understanding a biblical text. This introspective approach has much to commend it. (John Claypool, for instance, uses this approach with some effectiveness.) Other preachers, however, seem to regale themselves, not the congregation, by an overabundance of references to, “I,” “me,” and “my.” Personal illustrations can be a powerful source of illustrative material. However, personal illustrations are easily abused, usually by overuse. Clearly a syn thesis is needed. (Related to the use of personal illustrations in preaching is the problem of integrity. Because a personal illustration has emphatic power, some preachers relate all of their illustrations as if they were personally involved when they actually were not. No synthesis is needed here; just a dose of honesty!)

Synthesis is needed as to ·the objectives of illustrations in a sermon. Should an illustration arouse the emotions of the congregation? The question is often asked blandly so that the manipulated answer usually is, “Yes, there should be some emotional involvement. ” The question is much more complicated than that. How much emotional arousal of the congregation is enough? Will the emotionally aroused congregation be led or will it be manipulated and exploited? Is the purpose of sermonic illustrations to so emotionally involve the congregation that individual members of the congregation react or respond unthinkingly? There are preachers who can arouse, cajole, scold, and maneuver the ethos of a congregation by a sly arrangement of humor and tragedy in their illustrative materiel. Such preachers generally rationalize by claiming that they just do whatever it takes to “get people saved.” Other preachers try to avoid any emotional element in their sermons because of the abuses of emotionalism. Which view is the correct one? Clearly a synthesis is needed.

Dr. Northcutt admitted that his appreciation for illustrative material came “late” in his ministry. In his early and most impressionable years, he quietly noted that congregations generally resented sermons that were ” . . . long on stories and short on Bible. ” His early sermons are almost devoid of illustrative materials, especially anecdotes. Later, he realized that not all stories are unsuitable for sermons, but sermons that are all stories are unsuitable for preaching. From these early experiences, Dr. Northcutt was able to crystallize his own thoughts on illustrative materials. By the time he began teaching homiletics at Southwestern, he had synthesized that preaching ” . . . needs to paint pictures to help the congregation see truth as against just thinking about it. In a private conversation on January 16, 1984 (from which all of Dr. Northcutt’s direct quotes in this article are taken), Dr. Northcutt asserted, “Of all the qualities that contribute to good preaching, illustration is near the top.” In his preaching classes, Dr. Northcutt regularly advised his students to develop a sensitivity to the potential illustrative material that constantly surrounds us and then to develop an ability for “image making preaching.”

In honor of Dr. Northcutt’s forty-three years of teaching homiletics at Southwestern, this article will explore: A definition of illustrations for preaching; the value of illustrations in preaching; types of illustrations for preaching; sources for illustrations in preaching; and general principles for the use of illustrations in preaching.

Definition of Sermon Illustration

Most homiletics books (including books specifically on how to illustrate sermons) presume that every reader knows what a sermon illustration is. An additional presumption in some homiletics books is that every reader will agree that sermon illustrations come only in the form of stories. Many homiletics books define what an illustration should do, but rarely do they define what an illustration is. Spurgeon, for example, used an illustration to define what an illustration should do: “The chief reason for construction of windows in a house is . . . to let in light. Parables, similes, and metaphors have that effect, and hence we use them to illustrate our subject, or, in other words, ‘to brighten it with light’, for that is Dr. Johnson’s literal rendering of the word illustrate.“[1]Charles Haddon Spurgeon, The Art of Illustration (New York: W. B. Ketcham, 1894), p. 7. Often a homiletics author will share a bit of etymology, and we learn that the word “illustrate” comes from the Latin “illustare,” which means “to cast light upon.”

Robert J. Hastings made one of the most comprehensive attempts at defining what an illustration is:

What is an illustration? Frankly, we prefer the term “illustrative material, ” which includes far more than a story or anecdote. But for simplicity, we will simply say illustration. In its larger context, illustrative material includes personal experiences, anecdotes, snatches of poetry, statistics, humor, quotations, proverbs, fables, similies, object lessons, figures of speech, puns, biography, current events, hymn stories, epitaphs, acrostics, legends, drama, art, satire, sports, word pictures, picturesque speech, ad infinitum.

An illustration is a comparison or example intended to make clear or apprehensible, or to remove obscurity. Hence, if there is a statement we do not understand we say, “Give me an illustration of what you mean.”[2]Robert J. Hastings, A Word Fitly Spoken (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1962), p. 8.

Numerous students recently have complained that they do not know how to discern illustrative material in a sermon from the explanation of the text or the application of the text. (Many of them claim they do not know what an illustration is and whether or not they have used illustrative materials in their own sermons!) In an attempt to assist preachers who have either blindly followed their role models, or who were not exposed to good teachers of rhetoric, or who suffered some other gap in their education, this author offers a brief schematic description of how an illustration functions within the sermon.

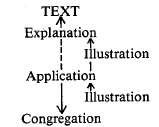

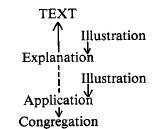

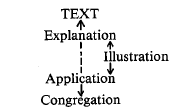

The sermon draws its substance from its biblical text. The sermon is developed (often with a rhetorical outline for the sermon structure) by use of the functional elements of preaching; explanation (exposition of the text), application (relating the text to the congregation), and argumentation (use of specific lines of reasoning to persuade or convince the congregation). Illustration is a special servant of explanation and application. Argumentation has its own specialized forms of illustrative material. Space is too limited to discuss these forms here.[3]For a study of argumentation as a functional element of preaching, see H. C. Brown, Jr., A Quest for Reformation in Preaching (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1968), pp. 55-70. (Dr. Northcutt agrees that illustration is a servant of explanation and application, but feels illustration is important enough to classify it as a separate functional element.) Explanation refers directly to the text. Application is built from the text and explanation of the text and refers directly to the congregation.

Illustration refers directly to either the paragraphs of explanation or application:

Illustration can also point forward to explanation and application:

Occasionally, an ideal illustration may cast light upon explanation and application at the same time:

A sermon illustration, then, is that material that casts light upon explanation and/or application in the sermon. Illustration has direct reference to explanation and application and indirect reference to the biblical text and the congregation.

Value of Sermon Illustration

As indicated in the introduction, the chief value of sermon illustration is to add appeal to the sermon; to ” . . . paint pictures to help the congregation see the truth . . .; ” to help the sermon “come alive. ”

Writers of books on homiletics and/or sermon illustrations have generally agreed on the value of sermon illustrations, although there is variety in their expression. Broadus saw the value of illustrations as: ornamental (adding beauty to the sermon); an excellent means for arousing attention; as a means of ” . . . exciting some kindred or preparatory emotion . . .” for the subject of the sermon; and as an assist for the memory of hearers.[4]John A. Broadus, A Treatise on the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons (New York: Hodder & Stoughton, 1870), pp. 227-28. Spurgeon suggested these values of a good sermon illustration: to make a sermon pleasurable and interesting, to enliven a congregation and quicken attention, to cast light upon the subject at hand.[5]Spurgeon, pp. 10-12. Sangster listed seven values of sermon illustrations: 1) they can make the message clear, 2) they ease a congregation, 3) they make the truth impressive, 4) they make preaching interesting, 5) they make sermons remembered, 6) they help to persuade people, 7) they make repetition possible without weariness.[6]W. E. Sangster, The Craft of Sermon Illustration (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1950), pp. 18-21. There seems to be consensus, if some difference in detail, among homiletics authors, on the value of sermon illustration. The consensus endures.

Sangster’s value number five above is significant. It is possible that illustrations are remembered because of their entertainment value – be it comedy or tragedy. It is more likely that the illustration was remembered because it related a biblical passage to the everyday life of the hearer. Jesus was masterful in this area. Think of the immediate pictures his words can bring to mind: “A sower went out to sow . . ., ” “A certain man had two sons. . . .” Jesus spoke about many everyday things: weddings, market places, birds of the air, lilies of the field, and sheep. All of these everyday items served as illustrations that “painted a picture ” and related a pro found truth.

The value of sermon illustrations to those who listen to sermons was underscored for this author recently. One of my doctoral students shared a respectful letter he had received from a member of his congregation. The letter suggested a need for appropriate sermon illustrations:

I do sense your earnest efforts and your eloquence at the pulpit. Yet, as I told you last Sunday, I felt that I should communicate with you, the slight sense of imperfection in your messages. As mentioned, I feel that it may be helpful, if you can incorporate everyday life-examples into your pulpit message. A concrete example, a life experience if used appropriately is more effective than a thousand words.[7]Letter dated January 17, 1984 to one of my Ph.D. students, Peter Chiu, from a member of his congregation in Austin, Texas. Quoted by permission from Mr. Chiu.

In fact ” . . . a thousand words ” may be not only less effective than a sermon illustration; they will likely be fatal to the attention and response of the listener.

There are preachers who do their work effectively with little or no use of sermon illustrations. These rare people have a gift for clear and forceful expression. To these people, Sangster has a word of caution: “Be quite sure that your denial of their (illustrations) use is not a defense of your inability to master this craft.”[8]Sangster, p. 23. H. Jeffs has well described the value of a sermon illustration:

Should . . . a preacher treat the congregation to an illustration that has a human touch in it, at once they prick their ears, and the illustration will be remembered, with the point illustrated, for years perhaps, whereas the “thoughtful sermon” as a whole will scarcely survive the following week.[9]H. Jeffs, The Art of Illustrating Sermons (London: James Clarke & Co., 1909), pp. 11-12.

Types of Illustrations for Preaching

Sermon illustrations can be divided generally into three broad categories as to type: 1) figures of speech, 2) anecdotes, and 3) personal experience. There are many subspecies under each of these three broad categories. Benjamin Keach listed thirteen different kinds of figures of speech in his massive book Preaching from the Types and Metaphors of the Bible.[10]Benjamin Keach, Preaching from the Types and Metaphors of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1972). His list includes these twelve that are often used in preaching:

metonymy– the use of the name of one thing for that of another to which it has some logical relation, as “the Book ” for the Bible.

irony– usually an outcome of events contrary to what was or might have been expected; could also mean a figure of speech in which the literal meaning of a word is the opposite of that intended, as when a preacher sarcastically describes Judas as “loyal.”

metaphor– a figure of speech in which a term or phrase is applied to something to which it is not literally applicable in order to suggest a resemblance, as when the Bible describes the Christian’s body as a temple.

synecdoche– a figure of speech by which a part is stated for the whole, or the whole for a part, such as “the cattle on a thousand hills.”

simile– a figure of speech directly expressing a resemblance of one thing to another, such as, “He was like a father to me.”

catechresis– a figure of speech intended to convey harshness, as in Lev. 26:30 where false gods are called carcasses.

hyperbole– an obvious exaggeration for effect, as when a preacher says, “The Bible became heavier than an anvil.”

allegory– an extended figure of speech in which one thing is said, but another thing is understood, as in Gal. 4:26-27.

proverb– a popular saying containing a familiar or useful thought, such as “honesty is the best policy.”

enigma– a figure of speech conveying something obscure or inexplicable, or containing a riddle, such as the enigmatic saying of Samson in Judg. 14:14.

types– denoting an example, such as “Isaac was a type of Christ.”

parable– a short story that conveys its meaning by a comparison or under the likeness of something comparable. Examples abound in the teachings of Jesus.

Anecdotes may be divided as to whether they are truth or fiction. An anecdote taken from the realm of truth may have many sources, but is usually in the form of a story. Sangster feels the veracity of an anecdote is always in question. That is a severe definition of the term. Anecdotes may relate to some actual incident or may obviously be the narration of some fictitious incident. Anecdotes that are true can be found everywhere. (A discussion of the sources for illustration material – including anecdotes – follows.) Anecdotes that are fictitious may be a parable, which was just described, or they may be fables. Fables are brief stories that contain a moral, often told with animals, inanimate objects, or imaginary persons as the characters. Fables are not as widely used in sermons today as they once were. Broadus, for instance, wrote: “Fables are so often alluded to in common conversation that we scarcely notice it, and the occasions are very numerous in which they might be usefully employed in preaching.”[11]Broadus, p. 239.

Personal experiences of the preacher may be communicated as an anecdote or even as one of the figures of speech mentioned above. Personal experiences have such a special appeal about them that it seems appropriate to mention them separately.

Personal experiences as sermon illustrations have, Dr. Northcutt says, “a special quality of witness and testimony – qualities which contribute to effective preaching.” These “qualities” include deep emotional, intellectual, spiritual involvement of the congregation with the preacher, and ultimately, with the truth the sermon is attempting to convey. A personal illustration brings the sermon to “life” in a way that no other type of illustration can. The personal experience illustration does not need to “paint pictures;” it is already a life portrait with which the congregation can empathize and literally “see the truth as well as just think about it.” Potentially, the personal experiences of the preacher may constitute the most powerful type of illustration available. A few words about their use will be shared in the final section of this article.

There are many subcategories that could be mentioned with reference to types of illustrations. This brief discussion, however, is representative of the major kinds of illustrative material used in preaching.

Sources of Illustrations for Preaching

In his preaching classes, Dr. Northcutt taught that the whole realm of human experience is the source for illustrations in preaching. Broadus came to the same conclusion: “Illustration of religious truth may be drawn from the whole realm of existence and conception.”[12]Ibid., p. 229. From these influences this author teaches: “There is no place where potential sermon illustrations are not.”

Since the sources for sermon illustrations are virtually unlimited, why, then, do many preachers agonize about finding them? For two reasons: either they are not sensitive to sermon illustrations that are all about them or it is not sermon illustrations in general that they need, but a particular kind of illustration that will be appropriate to the point of the sermon. Both situations relate to sources for illustrations in preaching.

Every preacher needs to develop a sensitivity system for illustrations. Some preachers are uniquely gifted with such a sensitivity. They find illustrations in incidents and conversations that other preachers never see. Most of us, however, must develop such sensitivity and there must be at least as many approaches to such development as there are experts on human behavior. Sangster suggests that a preacher’s sensitivity to illustrations can be built by noting that illustrations announce themselves in two voices: ” . . . one loud and heard by all; one whispered in the ear.”[13]Sangster, p. 49 When these “voices ” are noted, the preacher should write it down immediately. Then,

Don’t think about any particular sermon at this time. . . . It will “pull” the sermon off its course. Question it . . . inquire what the analogical lesson is. If it is stubborn be patient . . . . It will not resist you forever. At the last, it may come in a flash. . . . Reserve the illustration for that use.[14]Ibid., p. 50.

Other suggestions for developing sensitivity to illustrative material include: taking courses in photography or art, extensive reading, keeping a diary or journal of everything that happens or is said, and constantly asking questions of what is seen or read, especially the question, “Why?”. It also helps to ask a prolific preacher how he developed his own sensitivity to illustrative material. Dr. H. C. Brown, Jr. testified that he developed his own sensitivity to illustrations by toying with ideas, especially by “flipping them over.”

Dr. Northcutt reflects that his favorite source for illustrations for preaching are the Scriptures and personal experiences. Each of these two sources involves people and, therefore, has what journalists like to call “human interest.” Dr. Northcutt’s sermons generally include illustrations from both these sources. His sermons also abound in figures of speech, especially similes. Thus, in addition to Scriptures and personal experiences, Dr. Northcutt was able to use his own fertile mind as a source for sermon illustrations.

There are numerous other sources which can be cited only in general terms: biographies and autobiographies, history, fiction, poetry, art, music (hymns), current events, theological studies, sports, science, nature, specialized fields of study, travel, and human and personal observations (as distinguished from personal experiences). There are legions of subdivisions for each of these general divisions. It is important to note that “Illustrations which have come from primary and reliable sources are far more pertinent than illustrations from secondary or tertiary sources of unknown reliability.”[15]Brown, p. 59.

General Principles for the Uses of Illustrations in Preaching

There are multiple tensions to be acknowledged in the use of illustrations in a sermon. Illustrations are servants to explanation and application; however, illustrations may be the most remembered part of the sermon. Illustrations may serve by casting light upon a portion of the sermon; however, the light must not be so bright that it blinds the listeners to the truth it serves. Illustrations may serve by being ornaments that enhance the appeal of the sermon; however, these ornaments must not be trivial in relation to the truth they adorn. Illustrations may serve by bringing the sermon “to life”; however, illustrations must not be the only source of life in the sermon. Since illustrations are servants, they should fulfill a subservient role and not call attention to themselves.

J. H. Jowett summarized:

A lamp should do its own work. I have seen illustrations that were like pretty drawingroom lamps, calling attention to themselves. A real preacher’s illustrations are like street lamps, scarcely noticed, but throwing floods of light upon the road.[16]J. H. Jowett, The Preacher: His Life and Work (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doren & Co., Inc., 1912), p. 141.

The first principle in the use of sermon illustrations is to be sure there is an idea that is worth illustrating. Usually this is determined by noting something in the biblical text or in the sermon itself that is remote or just as familiar to the everyday experiences of the congregation. The illustration serves to make the less familiar cognizant to the congregation by the use of some analogy that is part of their lives or more familiar to them. Simply, any information that may not be easily understood by the congregation may be illuminated by an illustration that is easily understood by the congregation.

A second principle is to make a smooth introduction of the illustration. There are thousands of ways of doing this, depending upon the context and type of illustration being used. Perhaps it would be simpler to state this principle negatively: Avoid mechanical, trite introductions to illustrations. For example: “Let me illustrate . . ., ” “That reminds me of the time . . ., ” “Here is a story. . . .”

Third, good illustrations ought to be intelligible. This relates to the first principle. Dr. Northcutt feels that ” . . . a good illustration is in touch with the lives of the congregation. ” The illustration should relate to the congregation. The impact of an illustration is diminished or even lost when an illustration does not relate to the lives of the congregation.

A fourth principle: The illustration must be strongly related to the point it illustrates. An illustration ought to get to the point and not engender more points to be discussed.

Fifth, an illustration ought to be credible. The impact of an illustration is lost if the illustration is not believable. A congregation may be regaled occasionally by stories that dramatize miraculous occurrences. A steady diet of such illustrations or a steady overuse of superlative statements will be damaging to credibility. Sixth, illustrations should be appropriate to the truths they illustrate. This relates to principle number five. Cheap illustrations do not illustrate a profound truth.

Seventh, illustrations should be appealing and interesting. As has been noted, the use of a story with human interest is a primary way to develop an appealing illustration. Human interest puts the illustration in touch with life. Dr. Northcutt says,

When God decided to give truth to the world, He did it in the form of stories. The best of these stories involves a Person. The Person gave Himself supremely. The basic gospel is a story about that Person.

A final principle: Use a variety of types of illustrations. The varieties have already been discussed. It would be extremely difficult to indicate some ratio of anecdotes to figures of speech that would be proper for every sermon. It is just as difficult to indicate a ratio of illustrations per sermon. It is advisable to evaluate sermons before they are preached and to evaluate sermons that have been preached recently. This evaluation could provide some statistics as to the numbers and kinds of illustrations being used and offer a clue as to how many and what kinds of illustrations may be needed in future sermons.

An illustration is a servant within the sermon. The amount of space given even in this brief article tells us what an important servant illustrations can be. Whether this servant makes a brief appearance, as in a simile, or whether this servant appears throughout the sermon (as in the sermons of C. Roy Angell), the illustration is to fulfill a servant’s role. For an illustration to be the sermon would be like taking pride in one’s humility – the illustration and the humility cease to exist. When they cease to exist, the ministry they could have and should have fulfilled goes wanting.

Strive to use sermon illustrations effectively. Use sermon illustrations effectively by using them as windows to the sermon. Let them cast light, but not be the light unto themselves. Let them make contact with life, but not be the life themselves. Let them adorn the sermon, but not be the center of attention.

References

Southwestern Journal of Theology

To download full issues and find more information on the Southwestern Journal of Theology, go to swbts.edu/journal.