Learning to Preach from John Broadus

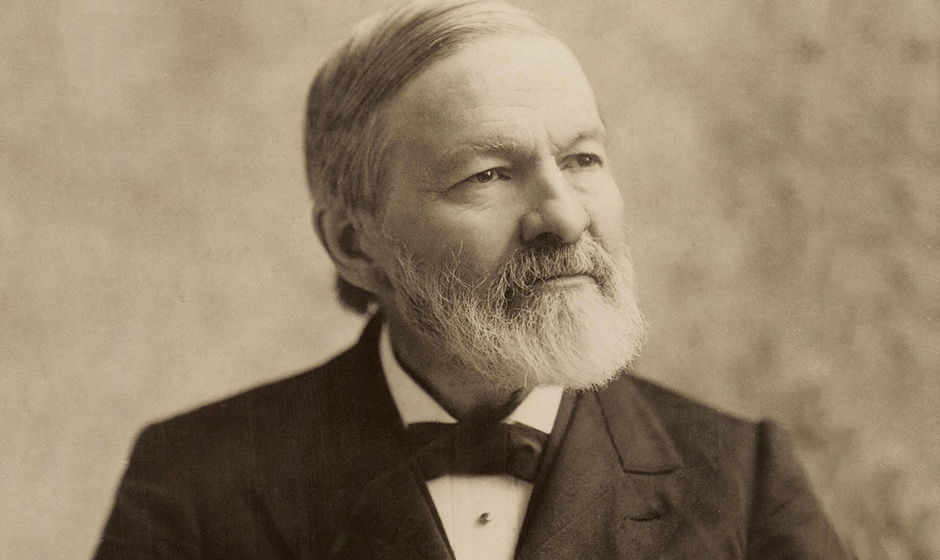

John Albert Broadus (1827–1895) is, as my preaching professor Dr. Matthew McKellar has said, the granddaddy of text-driven preaching. He had experience as a Greek and Latin tutor as well as a pastor. He also had pastoral experience as a chaplain, albeit sadly for the Confederacy. He was educated—receiving a Master of Arts from the University of Virginia in 1850—but was self-taught in the realms of theology and homiletics. He became one of the founding faculty of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, serving there during its transition from Greenville, South Carolina, to Louisville, Kentucky. He would even serve as the seminary’s president from 1888 until his death. During his lifetime, he was more well-known for his work in the New Testament, particular his commentary on Matthew.[1]John A. Broadus, Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew (London: Forgotten Books, 2012). He did translation work, preached in small churches, wrote Sunday School lessons, provided scholarly work on John Chrysostom in Schaff’s Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers.[2]John A. Broadus, “St. Chrysostom as a Homilist,” in Saint Chrysostom: Homilies on Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Thessalonians, Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, vol. 13 of A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, ed. Philip Schaff, reprint (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1994), v–vii.

He was the first professor of preaching in Southern Baptist life and wrote the first preaching textbook from a Baptist perspective, his Treatise on the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons.[3]Although numerous editions exist, I would encourage the reader to invest in A Treatise on the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons (Charleston, SC: Bibliobazaar, 2010). In terms of Baptist homiletics, he paved the way for the expositors and text-driven preachers who would come after him.[4]For more biographical information on Broadus, see David S. Dockery and Roger D. Duke, eds., John A. Broadus: A Living Legacy (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2008); Hughes Oliphant Old, The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church, Volume 6: The Modern Age (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 727–37; O. C. Edwards, Jr., A History of Preaching (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2004), 654–59. It is his magnum opus that provides us with, I believe, five principles necessary for preaching.

1. Pastor in order to preach.

Some readers may balk at this idea, and in the spirit of full disclosure, I must confess that I am not nor have ever been a pastor. However, there is a theological truth that leads me to argue for this. When we preach, we preach the word of God. Heaven speaks when we open the Scriptures. Yes, a pastor can bring Scripture to bear in his counseling, hospital visits, deacons’ meetings, etc. But there is something in the preaching event that cannot be replaced. Broadus writes:

Pastoral work is of immense importance, and all preachers should be diligent in performing it. But it cannot take the place of preaching, nor fully compensate for lack of power in the pulpit. The two help each other, and neither of them is able, unless supported by the other, to achieve the largest and most blessed results.[5]Treatise, 18.

Show your people that you care so that they will listen when they gather to hear God speak from you. Preach the word of God, so that when you shepherd your people to obey that word, they’ve seen your commitment to it each Sunday.

2. Commit to the expository method.

Broadus explains the difference between the three major classifications of sermons, what we may now call topical, textual or text-centered, and expository or text-driven. Broadus discourages using the topical method too frequently because:

Too often the text is only a starting-point, with which the sermon afterwards maintains, not only no formal, but no vital connection. Sometimes, indeed, it is made simply a motto, a practice of extremely doubtful propriety.[6]Ibid., 290.

If it is the word of God that we preach, then we must be diligent in maintaining that our sermons are based solely on the text. It is for this reason that Broadus champions the expository method. That is not to say that topical or textual sermons do not have the occasional pastoral warrant, but it is to say that text-driven preaching leads to a “vital connection” to the text being preached. And lest someone believe preaching expositionally is too difficult, hear Broadus’ advice:

One who now thinks this method of preaching unsuited to him, needs nothing but diligent study and practice, upon some such principles as have been indicated, to make his expository sermons very profitable to his hearers, and singularly delightful to himself.[7]Ibid., 318.

My paraphrase: If you can’t preach expository sermons, study and practice until you can!

3. Be possessed by your subject.

Broadus’ Treatise combines the disciplines of homiletics and rhetoric, so much attention is given to practical matters of delivery. But tucked away in his discussion of delivery is this gem:

And delivery does not consist merely, or even chiefly, in vocalization and gesticulation, but it implies that one is possessed with the subject, that he is completely in sympathy with it and fully alive to its importance; that he is not repeating remembered words, but bringing forth the living offspring of his mind.[8]Ibid., 444–45.

I must admit that Broadus’ conception of preaching is not the modern-day conception of text-driven preaching. When Broadus speaks of the subject, he means the core truth of the text being preached. In contemporary homiletical theory, we could say the “main idea of the text.” But for those of us committed to patterning our sermon of the text as much as possible, to be possessed by our subject means to be possessed by the text. So enamored with its truth and the God who inspired it that our very method of delivery communicates that we are convinced of its truthfulness and vitality. Our sermon becomes, not rote memorization or perfunctory performance, but the impassioned appeal to listening ears.

4. Preach the gospel in the Spirit’s power.

Preaching is serious business, and because it is serious business, it is stressful business. The preacher can become burdened down with the desire that his audience hears and believes in the gospel message he proclaims. When we do not see the tangible results of our preaching, it is easy to become discouraged and believe it’s all for nothing. Hear Broadus’ advice:

After all our preparation, general and special, for the conduct of public worship and for preaching, our dependence for real success is on the Spirit of God. And where one preaches the gospel, in reliance on God’s blessing he never preaches in vain.[9]Ibid., 504.

This applies to us in two ways. 1) We must make sure it is the gospel that we preach, not our own opinion. Each text, each sermon, should be used to make our way to herald the gospel. 2) Our reliance is on the Spirit’s empowering, not our own strength. When we submit ourselves to these two, we serve the Lord in faithfulness. Whether the numbers follow or not, this is success.

5. Preach with your life, not just your sermons.

When I first read Treatise, its final words have never left me. I am still captivated each time I read them:

What a preacher is, goes far to determine the effect of what he says. There is a mediæval proverb, Cujus vita fulgor, ejus verba tonitrua. If a man’s life be lightning, his words are thunders.[10]Ibid.

If our life does not match our preaching, our congregation need not listen. Lightning flashes before the thunder rolls. Our integrity must precede our preaching. And when it does, it only empowers our sermon.

Aaron S. Halstead serves as the Administrative Assistant for the Professional Doctoral Office at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary and as the Editorial and Content Manager for Preaching Source. He is also a PhD student in Southwestern’s School of Preaching.

References