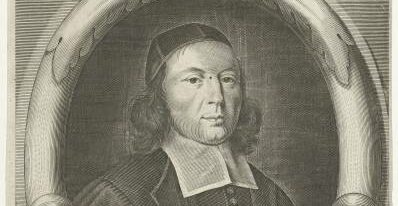

GREAT PREACHERS AND THEIR PREACHING: JOHN FLAVEL

The following article is part of a series of articles that will traverse church history to examine the preaching of great preachers.

John Flavel (1627–1691) was one of the most popular preachers among the sevententh-century English Puritans.[1] He employed a very simple method of preaching, deriving his doctrines from Scripture, and then encouraging his readers to pursue a heart-felt application of those doctrines to all of life. By the time of his death in 1691, he had ministered for over forty years. “I could say much, though not enough, of the excellency of his preaching,” writes one of his congregants, adding, “that person must have a very soft head, or a very hard heart, or both, that could sit under his ministry unaffected.”[2]

Thankfully, Flavel gave a considerable amount of his time to writing and publishing his sermons. These were compiled after his death, and his complete works were printed five times in the eighteenth century, and multiple times in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It has been said that “there are few writers of a more experimental, affectionate, practical, popular, and edifying character than Flavel.”[3]

Much of Flavel’s success as a preacher is explained by his familiarity with life’s manifold sorrows and sufferings. He ministered out of his experience of great personal loss. His parents died of the plague, contracted while imprisoned for nonconformity.[4] He witnessed the death of his first three wives along with several children. He was ejected for nonconformity in 1662, and generally harassed throughout his ministry. On one occasion, he managed to escape arrest by plunging his horse over a cliff into the sea and swimming to shore. Factoring in the strain of demanding pastoral duties and wearying doctrinal disputes, coupled with the challenges of living without modern comforts and amenities, Flavel was deeply acquainted with suffering. By his own account, it was “joy” that “upheld and fortified” him throughout life’s arduous journey.[5]

Flavel defined Christian joy as “the cheerfulness of our heart in God,” arising from “the sense of our interest in Him and His promises.”[6]

The “sense” of our interest in God is rooted in our union with Christ through faith. “All the comforts of believers,” says Flavel, “are streams from this fountain.”[7] In his preaching, Flavel aimed to impress this knowledge of Christ upon the soul. “All other knowledge, however pleasant and profitable, is not worthy to be named in the same sentence with the knowledge of Christ.”[8] He encouraged his hearers to cultivate a “sensible” and “practical” knowledge of Christ; that is, a knowledge that has its “seat in the heart.”[9]

The “sense” of our interest in God’s promises is fixed upon all that awaits us in glory. As Flavel makes clear, the presence of sin disrupts our enjoyment of God at present. At glorification, however, we will be free from this burden. We will be like Christ and, therefore, able to commune with God to the fullest capacity of our souls. This will result in unparalleled delight, as we rest fully in Him. Flavel explains, “To see God in His Word and works is the happiness of the saints on earth, but to see Him face to face will be the fullness of their blessedness in heaven.”[10] This is not primarily a sight of the eye, but a sight of the soul. In short, the beatific vision means that the image of God will be restored in us. The mind will perceive God as the greatest good, and the affections will love God as the greatest good. We will find our complete rest in God, and this will be our heaven.[11]

This emphasis on Christian joy (rooted in the “sense” of our interest in God and His promises) figured prominently in Flavel’s ministry. He was convinced that one of his chief duties was to cultivate such joy among his hearers. In his preaching, he sought to bring his hearers into vital contact with Jesus Christ, declaring, “Look on Him in what respect or particular you will; cast your eye upon this lovely object, and view Him in anyway; turn Him in your serious thoughts which way you will; consider His person, His offices, His works, or any other thing belonging to Him; you will find Him altogether lovely.”[12] As we gaze upon Christ’s loveliness, we behold God’s goodness, faithfulness, lovingkindness, holiness, etc. For Flavel, this is “the life of our life, the joy of our hearts; a heaven upon earth.”[13]

[1] For details of Flavel’s life, see The Life of the Late Rev. Mr. John Flavel, Minister of Dartmouth, in The Works of John Flavel, 6 vols. (London: W. Baynes and Son, 1820; rpt., London: Banner of Truth, 1968), 1:i–xvi.

[2] As quoted in Flavel, Works, 1:vi.

[3] Edward Bickersteth, as quoted in Iain Murray, “John Flavel,” Banner of Truth, no. 60 (Sept 1968): 3–5.

[4] In 1662, Parliament passed an Act of Uniformity according to which all who had not received Episcopal ordination had to be re-ordained by bishops. In addition, ministers had to declare their consent to the entire Book of Common Prayer and their rejection of the Solemn League and Covenant. As a result, approximately 2,000 ministers left the Church of England. They became known as “dissenters” or “nonconformists.”

[5] Works, 2:244–45.

[6] Works, 4:429.

[7] Works, 1:35.

[8] Works, 1:34.

[9] Works, 1:131.

[10] Works, 2:282.

[11] Works, 2:284.

[12] Works, 2:215.

[13] Works, 4:250.

J. Stephen Yuille serves as Professor of Church History and Spiritual Formation at Southwestern Baptist Theological seminary in Fort Worth, Texas.