The Book of Jeremiah

The book of Jeremiah is neither a biography nor auto biography of Jeremiah, nor is it a carbon copy of all his sermons. it is all of these things and more, with the various materials being joined together in what seems to be a hap hazard fashion. It has often been called one of the most unreadable books in the Bible. Perhaps this factor prompted Elmer A. Leslie to begin his commentary on Jeremiah by saying, “The aim of this volume is to make the reading of the entire book of Jeremiah an intelligible, interesting, and inspiring experience.”[1]Jeremiah (New York: Abingdon Press, 1954), p. 7 Whether or not Leslie accomplished his purpose must be left for each individual reader to decide, but we all can admire him for attempting such a worthy, ambitious, and difficult task. Scholars who have dealt with this book have almost “with one accord” called attention to the difficulties in reading and understanding it. Raymond Calkins said that “in their present form it is not too much to say that, without a guide, the prophecies of Jeremiah are unintelligible. Even the earnest and thoughtful student soon gets lost and is unable to find his way.”[2]Jeremiah the Prophet (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1930), p. vii.

A prominent preacher of a generation ago said, As a lad I started to read the Scripture through ac cording to the familiar schedule, three chapters each week-day and five on Sunday, by which we were assured that in a single year we could complete the reading of the Book. I got safely through Numbers and Leviticus, even Proverbs did not altogether quench my ardor, but I stuck in the middle of Jeremiah and never got out. I do not blame myself, for how can a boy read Jeremiah in its present form and understand it?[3]Harry Emerson Fosdick, The Modern Use of the Bible (New York: The Macmillian Company, 1942), p. 21.

H. Cunliffe-Jones said that “no one can pretend that the book of Jeremiah is an orderly book.”[4]Jeremiah (“Torch Bible Commentaries” New York: The Macmillan Company, 1961), p. 15. And George Adam Smith called it a “conglomeration of prophecies.”[5]Quoted by Calkins, p. xv. A. S. Peake said of this book:

No clear principle seems to have determined its arrangement, so that any one who reads the book straight through finds himself in a state of constant bewilderment as he moves backwards and forwards along the prophet’s career, or, still worse, had no clue to the situation of the period of the prophet’s life reflected in the portion he may be reading.[6]Jeremiah (“The Century Bible” Vol. 1, London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1910), p. 48.

H. Wheeler Robinson, commenting on the difficulty in reading the book of Jeremiah, said that for a reader who comes to this book for the first time the first chapter would be intelligible and interesting enough and that the main theme of the second and following chapters would also be apparent. But soon the reproach of the people for their disloyalty would become monotonous.

If our reader were of the steadfast sort, . . . he might get as far as the thirteenth chapter, . . . or even as far as the eighteenth, . . . and the reader might be pardoned for an instinctive gratitude, in reading the twentieth chapter, that something should happen at long last, even though it is that Jeremiah is beaten and put into the stocks. This is all that has been told of his life since his call under Josiah; yet, in the twenty-first chapter, we find ourselves in the reign of Zedekiah and the prophet is an old man, with the siege and destruction of Jerusalem close at hand. But, in the twenty-fifth chapter, we are carried back some sixteen years into the reign of Jehoiakim. I think our puzzled reader would before this have stolen a glance at the end to see how many more chapters there were, and to learn, perhaps with dismay, that there were as many as there are weeks in the year.[7]The Cross in the Old Testament (London: SCM Press, 1955), p. 124.

Perhaps all of the quotations above fit all too well the experience of the average reader of Jeremiah’s book. How ever, this situation does not need to persist. If the average person can be prepared beforehand for what he will encounter in the book of Jeremiah, the experience of reading this book can truly become an “intelligible, interesting, and inspiring experience.” It is the purpose of this article to attempt to prepare the reader for what he will encounter in the book of Jeremiah and to give him some guides to help make his experience more meaningful.

Difficulties in Reading the Book of Jeremiah

If a person comes to the book of Jeremiah starry-eyed, naively thinking that he can read it as quickly and as easily as a Mother Goose story, he is destined for a severe shock. Many of the ideas, people, and places in this book will be strange and unfamiliar, and the reader must always be prepared to change the depth and direction of his thinking with out notice. Therefore, if the reader of Jeremiah’s book is on his guard, always alert, constantly observant, knowing that difficulties will arise, he is well on his way to an under standing of the book.

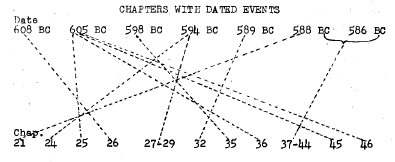

What are some of the difficulties that one is apt to meet in reading the book of Jeremiah? Perhaps one of the most serious difficulties in the book is its lack of any consistent chronological arrangement. To be sure, certain parts of the book are arranged chronologically. For example, chapter one tells of the prophet’s call which logically should come first. Chapters 2-6 seem to contain material appropriate to the prophet’s early ministry, and chapters 37-44 (telling of the siege and fall of Jerusalem and of Jeremiah’s fate after the fall) are in excellent chronological order. But two widely separated chapters (7 and 26) evidently describe the same event (Jeremiah’s temple discourse) which took place about 608 B.C. Many other chapters describe dated events which are not given in a proper chronological sequence.

Chapters with Dated Events

The above chart presents graphically the disarray in the chronological arrangement of the dated material in the book of Jeremiah.

But if the chapters which are dated are confusing, one only has to observe that more than half of the chapters in the book (1-20, 22-23, 30-31, 33, 47-51) have no dates at all to realize the real difficulty of the chronological arrangement of this material. The reader is left to determine on the basis of internal evidence where each unit of undated material should be placed.

Another difficulty in reading the book of Jeremiah is the lack of any consistent topical arrangement in the book. Here again we cannot say that there is no topical arrangement in the book. Chapters 1-25 are largely oracles of doom; chap ters 30-33 are messages of hope; and chapters 46-51, oracles against foreign nations.

But if the principle of arrangement be topical (and so it would seem in good part to be), it must be said that it is not consistently carried out. For Chaps. 1-25, mostly of doom, do contain oracles of hope (e.g., 3 :11-18, 16 :14-15, 23 :1-8), and also biography (e.g., 19:14-20:6); Chaps. 30-33, mostly of hope, are nevertheless not without oracles of doom (32: 28-35). The impression of disarray with which one begins is only strengthened.[8]John Bright, “The Book of Jeremiah,” Interpretation, IX (July, 1955), 264).

One of the most disturbing things about reading the book of Jeremiah is the way in which the author or editor frequently changes subjects without warning to the reader. For example, one may be reading of the coming of the foe from the north (6:22-26) when suddenly he is plunged into a passage about Jeremiah’s being an assayer or a tester of his people (6 :27-30). Chapter 17 is a good example of frequent changes of subject matter without warning. One recent expositor of this chapter entitled it “Miscellaneous Materials” (17:1-27). He says that the chapter has no central theme and may be analyzed as follows:

(a) a statement of the prophet that because Judah’s sin is engraved on the hearts of her people and in the cultus, she must go into exile and lose her treasures (Vss. 1-4); (b) a psalm contrasting trust in flesh and trust in God (Vss. 5-8); (c) a proverb on the deceitfulness of the heart and God’s knowledge of it (Vss. 9-10… ) ; (d) a proverb on the transitoriness of ill-gotten wealth (Vs. 11); (e) a fragment on the sanctuary (Vs. 12): (f) a brief prayer on the fate of those who forsake the Lord (Vs. 13); (g) one of the “confessions” of Jeremiah (Vss. 14-18); (h) a Deuteronomic passage on sabbath observance (Vss. 19-27).[9]James Philip Hyatt, Jeremiah (“The Interpreter’s Bible,” Vol. V, New York: Abingdon Press, 1956), p. 949.

The examples above are given to show that the book of Jeremiah is not always in chronological or topical order. Knowledge of this fact may not make the book any easier to read, but it should alleviate the shock and confusion which such phenomena are likely to produce.

Another difficulty in reading the book of Jeremiah stems from the fact that it contains various types of literature. One who reads this book in its original language, or in a modern version, or carefully in the King James Version cannot fail to detect the different types of material it contains. The book is partly poetry and partly prose, partly oracles and partly biography. Sometimes Jeremiah speaks for himself in the first person; sometimes he speaks for God in the same person; sometimes Jeremiah is referred to in the third person.

John Bright says,

Few students today fail to realize the importance of attention to literary form for understanding and interpreting the books of the Bible. Indeed, the necessity of this should be obvious. For example, he who interprets a. novel, a play, and essay, a history, a lyric poem, as if they were exactly alike will not get very far. The interpretation of any book is controlled by the type of material it contains. And so it is in the Bible.[10]p. 264.

Many passages in the book of Jeremiah are poetry. This fact has been known since the days of Robert Lowth and the publication of his Oxford lectures, De Sacra Poesi Hebrae orum Praelectiones Academicae,[11]See T. C. Gorfon, The Rebel Prophet (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1932), p. 160. in 1753 and is immediately evident to the reader of a modern version of the Bible.

George Adam Smith said:

Many passages read as metrically, and are as musical in sound, and in spirit as poetic as the Psalms, the Canticles, or the Lamentations. Their language bears the marks that usually distinguish verse from prose in Hebrew as in other literatures. It beats out with a more or less regular proportion of stresses or heavy accents. It diverts into an order of words different from the order normal in prose. Sometimes it is elliptic, sometimes it contains particles unnecessary to the meaning-both signs of an attempt at metre. Though almost constantly unrhymed, it carries alliteration and assonance to a degree beyond what is usual in prose, and prefers forms of words more sonorous than the ordinary.[12]Jeremiah (4th rev. ed.: New York: Harper and Brothers, 1929), pp. 31-32.

There can be no doubt that much of the book is poetry. In fact, Bernard Duhm, a German scholar at the beginning of this century limited Jeremiah’s own work to sixty short poems, all written in the same three-two accented lines.[13]See ibid., p. 40. Perhaps no serious scholar today would limit Jeremiah’s genuine material to the poetry of the book,[14]John Bright, “The Date of the Prose Sermons of Jeremiah,” Journal of Biblical Literature, LXX (March, 1951), 15-35. but every scholar would insist on the importance of a correct identification of the literary type of a passage to its proper interpretation.

One other difficulty in reading the book of Jeremiah is the lack of explanation of any historical or sociological details. The author never stops to explain the events or customs he mentions because such explanations would have been unnecessary for his immediate readers, but they would be invaluable for us who read his book 2,500 years later. For example, more than 110 different individuals are named in this book without any reference to their identity, except, perhaps, the name of their father or son or the political or ecclesiastic office they held at the time. More than 65 different places (towns, countries, rivers, etc.) are referred to in the book, usually without identification. There are very few narratives in the book which would help orient a modern reader. These factors, along with many others which might be mentioned, present real obstacles to an easy reading of the book of Jeremiah. But in spite of all these difficulties we believe that the book is of infinite value and makes every effort to read it intelligently immeasurably worthwhile.

A Guide through the Book of Jeremiah

Any attempt to outline the book of Jeremiah must result in only an approximate division of the text. Sharp and clear lines of demarcation are almost wholly lacking. How ever, certain broad divisions of the text may be observed along with some smaller units or groups of material within the larger divisions. The main divisions in the book come at the end of chapters 1, 25, 45, and 51.

Chapter 1 is introductory and contains an account of the prophet’s call and commission. Chapters 2-25 are for the most part a collection of Jeremiah’s oracles or prophecies (with some biographical material) down to 605 B.C. (25:1). However, there is some material in this section (2 25) later than 605 B.C. (e.g., chap. 21:1-10 must be dated about 588 B.C.).

Chapters 26-45 contain biographical material primarily, with some excerpts from Jeremiah’s sermons after 605 B.C. (chap. 26 does tell of an event which occurred in 609 B.C.), A cursory glance over these chapters in a modern version of the Bible reveals that they are, in contrast to chapters 2-25, mainly prose and are written in the third person rather than the first or second person.

Chapters 46-51 are prophecies against foreign nations. In the Septuagint this material is found after 25:13; however there the order of the oracles is different from that preserved in the Hebrew and English versions.[15]For a good discussion of the Hebrew and Septuagint editions of Jeremiah see F. C. Eiselen, The Prophetic Books of the Old Testament, Vol I, (New York: The Methodist Book Concern, 1923), pp. 255ff.; S. R. Driver, Introduction to the Literature of the Old Testament (9th rev. ed., Edinburg: T . and T. Clark, 1829), p. 269; and Smith, pp. 11-19.

Chapter 52 is an appendix added to the book to show how some of the prophecies of Jeremiah were fulfilled in the fall of Jerusalem and the exile of many Jews. It ends on a note of hope with the account of the release of Jehoiachin from prison in 516 B.C.[16]Hyatt, p. 1137.

From the above survey it can be observed that the date 605 B.C. was a turning point in the life of Jeremiah and a dividing point of his book. In 605 B.C. the battle of Carchemish was fought between the forces of Pharaoh Necho of Egypt and Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon. Its outcome tipped the balance of power of the ancient world in favor of the Babylonians for the next seventy years.

Although Jeremiah had been a prophet for twenty-one or twenty- three years (626-605 B.C.), it is altogether possible that until this time he had made no effort to preserve any of his messages in writing (23:5; 36:1). George Adam Smith sees the victory of Babylon over Egypt at Carchemish in the spring or summer of 605 B.C. as the human factor which led Jeremiah to put his messages into writing.

The cardinal event was Nebuchadrezzar’s victory over Necoh at Carchemish in 605 or 604 with its assurance of Babylonian, not Egyptian, supremacy throughout Western Asia. Such confirmation of the substance of Jeremiah’s prophecies of the past twenty-three years was that Divine signal which flashed on him, to reduce those prophecies to writing and have them recited to the people by Baruch.[17]Smith, pp. 177-78.

W. F. Lofthouse believes that Jeremiah’s reason for writing his first scroll in 605 B.C. was that he had been banned from entering the Temple.[18]Jeremiah and the New Covenant (London: Student Christian Movement, 1925), p. 120.. See also Hyatt, p. 967. Yet, he urgently needed to speak to the people, since he was convinced of the ruin which was about to fall on them. Since he could not go to speak personally to the people, he would write the messages which he had already spoken and, as the Lord said to Jeremiah, “It may be that the house of Judah will hear all the evil which I intend to do to them, so that everyone may turn from his evil way, and that I may forgive their iniquity and their sins” (36:3, R.S.V.),

Regardless of the immediate occasion for Jeremiah’s turning to writing as a means of prophesying, we can be certain that the the was 605 B.C. (36:1). The battle of Carchemish was for Jeremiah and his book what the fan of J erusalem was for the book of Ezekiel. It divided the book into two’ almost equal parts (1-25; 26-52). The first half of the book of Jeremiah (1-25) contains material, for the most part, from the period of 626-605 B.C., while most of the material in chapters 26-52 can be dated after 605 B.C. The material in the first half is usually undated; the material in the second half is well dated. Thus, although no sharp dividing lines can be seen in the book of Jeremiah, certain general boundaries are clear.

I. Jeremiah’s Call and Commission (1:1-19)

This is perhaps the clearest and most familiar chapter in the book of Jeremiah and is most significant. It sets the stage and pattern for the rest of the book. It indicates the prophet’s idea of God (God is sovereign), the relationship between himself and God (a dialogue), and the type of minis try he was to have. He was to be a prophet to the nations “to pluck up…arid to build” (1:10).

II. Jeremiah’s Prophecies before 605 B.C. (2:1-25:38)

This is the most difficult section in the book to outline, since it is made up largely of excerpts of sermons Jeremiah preached from 626-605 B.C., along with a number of his ”confessions” (11:18-23; 12:1-6; 15 :10-21; 17:12-18; 18:18-23; 20:7-18). There is no discernible progression of thought in this section. However, there are small groups or units of material bound together by a common theme.

1. Israel’s unfaithfulness and God’s call to repentance (2:1-4:4). This passage contains some of the earliest material in the book of Jeremiah and probably reflects the conditions in Judah before Josiah’s reform in 621 B.C. Israel’s sin is described as unfaithfulness to God expressed mainly in the worship of idols (2:28). Figures of speech abound in this passage. Stanley Hopper calls attention to seven similes of Israel’s defection in 2 :20-29. Israel’s defection is compared to (1) an ox that breaks the yoke, (2) a harlot, (3) a choice vine turned degenerate, (4) a stain of guilt that cannot be re moved with soap, (5) a restive young camel, (6) a wild ass, and (7) a thief, “who, when caught, retains nothing of that which he stole and knows only the deepening chagrin of penalty, frustration, impotence, and shame.”[19]Stanley R. Hopper, Jeremiah (“The Interpreter’s Bible,” Vol. V, New York: Abingdon Press, 1956), pp. 818-21.

Chapter 3 :1-4 :4 is a plea for Israel’s repentance. Although 3:14b-18 fits into the theme of the rest of the passage, it is prose and is generally thought to be postexilic.

2. The evil from the north-and within (4:5-6:30). This poetic section (4:5-6:30) represents a relatively large block of prophecies generally ascribed to the prophet’s own work around the theme of the “foe from the north” referred to in 1:3ff. James H. Gailey has called attention to the fact that Jeremiah had a great deal to say about the coming invasion of Judah, “but he also spoke of an inner world where the conflict is in terms of thoughts, emotions and choices.”[20]James H. Gailey, Jr., “The Sword of the Heart,” Interpretation, IX (July, 1955), 294. These two areas-the external events and their influence on the heart-can never be separated. Any expositor of a passage of scripture such as the one before us must be constantly aware of these two factors. More than three fourths of this passage is given to describing actions, conditions, and situations which could be seen or visualized by the eye of an observer in Jerusalem. At most only one-fourth of the material deals with the “heart” or its inner conditions and motives.[21]Ibid.

The identification of the “foe from the north” has been the subject of much discussion. Earlier scholars were confident that the Scythians were the foe.[22]See Smith, pp. 110ff. Others believe that the foe refers to the Babylonians.[23]See Hyatt, p. 779. Adam Welch puts all references to the “foe from the north” in the eschatological category.[24]Adam C. Welch, Jeremiah, His Time and His Work (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1951), pp. 110ff.

Perhaps an easy solution will never be found to this problem. However, it is altogether probable that during his early ministry Jeremiah associated the “foe” with the Scythians, but by the time the .prophecies were written no one could have had any doubt about the identity of the enemy.

For Jeremiah, however, the significant fact was not whether the sword was to be wielded by the human hands of Scythians, Medes, Chaldeans, or any combination of these. His very vagueness on this question should call attention to the precision with which he points to the true Wielder of the sword. At least five times in the passage under consideration the prophet speaks unmistakably for God in substance a:s at 5:15, “Lo, I will bring a nation upon you from far, 0 house of Israel, saith the Lord” (Cf. 4:(3 and 12; 6:19 and 21). It should be clear from these statements that what is important to Jeremiah is an instrument over which men have only incomplete control. He sees the coming destruction as an instrument in the hand of God.[25]Gailey, p. 299.

3. False and true religion (7:1-10 :25). The sensitive reader will recognize a definite break between the poems of chapters 4-6 and the prose of chapter 7 and parts of chapters 8 and 9. Not only has there been a change in style (which may be due to the hands of an editor), but there has also been a change in time (from the reign of Josiah [640-609 B.C] to that of Jehoiakim [609-598 B.C]. Josiah, on the basis of the Book of the Law (probably Deuteronomy) which was found in the Temple (2 Kings 22:8 ff.), tried to reform the religious and moral life of his people. He banned the worship of idols, specified Jerusalem as the only legitimate place of worship, and commanded that all the regulations of the law be kept. The reform seemed not to get below the surface, and upon the death of Josiah, the people, along with the new king Jehoiakim, seemed to return to an idolatrous condition worse than before.

The unity of this section (chaps. 7-10) is by no means certain or clear, but it can be discussed around the theme of the false and true religion. Jeremiah points out the people’s false idea of the Temple (7:1-15), their worship of false gods-the queen of heaven and other idols (7 :16-20, 30-34), their false idea of sacrifice (7:21-29), and their false idea of wisdom (8:4-13; 9:12-16, 23-26). Such false religion results in moral depravity (9 :2-9), sorrow and grief (8 :18-9 :1), and invasion and destruction (8:14-17; 9:10-11; 10:17-25).

The picture of the true God is set out in a passage which contrasts Yahweh, the true God, with the idols of the nations (10 :1-16). On the basis of style and on the ground that the people addressed seem to be in captivity (10 :2), this passage is denied to Jeremiah by most scholars. It does interrupt the context of 9 :26 and 10 :17. Four verses are omitted from this passage in the Septuagint and another verse is rearranged there. We must admit that this passage presents serious textual and contextual problems, but the message is a comforting and assuring one:

There is none like thee, 0 Lord;

thou art great, and thy name is

great in might.

But the Lord is the true God;

he is the living God and

the everlasting King.

At his wrath the earth quakes,

and the nations cannot endure

his indignation (10:6, 10, R.S.V.).

4. Jeremiah and the covenant (11:1-12 :17). Chapters 11 and 12 seem to center around Jeremiah’s relationship to the Deuteronomic reform in 621 C. It seems that at first Jeremiah supported the reform (11:1-8), but with the death of Josiah he saw his people break the covenant again (11:9-13). This reaction by the people resulted in God’s abandoning his people, at least for a while (11:14-17). It would seem that Jeremiah was persecuted by his own family and friends in Anathoth, possibly because of his support of the reform which resulted in their disestablishment (11:18-23; 12:5-6). The remainder of the passage deals with Jeremiah’s and Yahweh’s laments (12:1-4, 7-13), along with a conditional promise of the restoration of Judah’s evil neighbors (12:14-17).

5. Parables and warnings (13:1-27). This chapter is made up of five parts joined together by a dimly defined theme of the pride of Judah. The first two parts are parables in prose; the other three are warnings in poetry. The Hebrew prophets often used symbolic actions as a part of their pro Isaiah is said to have “walked naked and barefoot” for three years as a sign against Egypt and Ethiopia (Isa. 20:3), and Ezekiel is said to have lain on his left side three hundred and ninety days and on his right side for forty days to represent the exile of the two parts of his country (Ezek. 4:4-6).

Jeremiah makes much of prophetic symbolism. The first two parables of this chapter are good examples. (1) The parable of the waistcloth (13:1-11) is designed to show the ruin which will come to Judah by trusting in Babylon and ‘”drinking the waters of the Euphrates” (cf. 2:18). (2) The parable of the wine-jars (13:12-14) is Jeremiah’s first sketch of his figure of the cup of the wine of the wrath of God which the nations are to drink (see 25:15-28; 51:7). Jeremiah probably picked up a commonplace saying, designed to ex press confidence in prosperity ahead, and turned it into a symbol of destruction. (3) Jeremiah’s warning against Judah’s false pride (13:15-17) is “one of the priceless jewels of Hebrew literature.”[26]Hopper, p. 924. It expresses Jeremiah’s grief because his people cling to their false pride and do not give glory to God. “They are like travelers on the mountainside caught in a dark cloud. While they wait for the cloud to pass, and the light to come again, the night comes upon them and plunges them into utter darkness.”[27]Cunliffe-Jones, p. 112.

The last two passages in chapter 13 are a lament over the young king Jehoiachin and his mother (13:18-19) and ‘a description of the shame of Jerusalem pictured as a shepherdess who has forsaken her flock (13 :20-27).

6. Drought, sword, and famine (14:1-17:27).-Chapters 14-17 consists of a series of undated, loosely connected oracles concerning dismay, disobedience, and defeat. The occasion of the first prophecy was a terrible drought which the people interpreted as being due to their iniquities (14:7). The prayer of the people and Jeremiah’s intercession both are rejected (14:10-15 :9). In chapter 15:10-21 the prophet gives frank expression to his bitterest feelings against God. “The Lord’s reply shows that the prophet needed to repent and to be careful to speak only what was true.”[28]Hyatt, p. 939. The seriousness of Israel’s sin is pointed out dramatically in chapter 16 when Jeremiah is forbidden to marry and in chapter 17 in his expression, “The sin of Judah is written with a pen of iron; with the point of a diamond it is engraved on the tablet of their heart, and on the horns of their altars” (17:1, R.S.V.). In this section we meet for the first time a favorite expression of the prophet: “the sword, the pestilence, and the famine” (cf. 14:12; 21:7, 9; 29:17, 18; 32:24, 36; 34:17; 38:2; 42 :17, 22; 44:13).

7. Lessons from the potter (18:1-20 :18).-Chapters 18-20 are composed of various types of literature around the common themes of the potter’s vessels and national apostasy The passage 18:1-12 is a prose section in which God’s sovereignty is graphically described in terms of the potter’s sovereignty over his clay. The passage 18:13-17 is a poetic expression of the unnaturalness of Israel’s sin. The passage 18:18-23 records Jeremiah’s bitterest prayer for vengeance on those who were plotting against Chapters 19:1-20 :6 are a prose account of Jeremiah’s breaking a potter’s vessel as a symbol of the judgment of 7-18 we come to the last of Jeremiah’s “confession.” It is the saddest and bitterest word of all, yet it is one of the most important passages in all prophetic literature in revealing the secrets of the prophetic consciousness.

8. Bad kings, false prophets, and good exiles (21 :1-24: 10). At chapter 21 the fog in the book of Jeremiah begins to lift. We have not yet reached unlimited visibility, but certain events and people are clearly discernible. No dates are given in this section (chaps. 21-24), but certain well known kings are named. In fact, chapters 21:1-23:8 are mes sages directly to or about the last kings of Judah: Zedekiah (21:3-7), Shallum (22:10-12), Jehoiakim (22:13-19), and Jehoiachin (Coniah, 22:24-30). Other prophecies are directed to the house of the king of Judah or the house of David (21:11-12), and still others predict the raising up of ideal rulers or a messianic king (23:4-6).

Jeremiah had more to say about false prophets than any other prophet,[29]Ibid., p. 990. probably because he saw the terrible tragedy which lay just ahead and he knew that the responsibility for the plight of his people lay most heavily on the shoulders of false religious leaders and evil rulers. Chapter 23:9-40 is a classic passage on the false prophet.

Jeremiah’s understanding of history is nowhere set out so forcefully as in chapter 24 :1-10. Contrary to public opinion, Jeremiah believed that the Jews who had been taken captive to Babylon in 597 B.C. with Jehoiachin represented the “remnant” rather than the ones who had been left behind in Jerusalem.

9. A summary warning to Judah and the cup of God’s wrath for the nations (25:1-38). Chapter 25:1-14 represents a summary of Jeremiah’s preaching for twenty-three years, in which he warned the people that, because of their constant refusal to repent, the enemy from the north was drawing near. This passage is quite different in the Septuagint.[30]Cf. ibid., p. 999 and John Skinner, Prophecy and Religion (Cambridge: The University Press, 1936), pp. 240-41.

Jeremiah was a realist. He knew the sins of his people would be punished. The foe from the north had to come, but that was not all. He knew that Yahweh was the God of the whole world, and those nations who had administered the cup of Yahweh’s wrath to Israel would themselves have to drink of it (cf. 25:15-38).

III. Some Significant Events in the Life of Jeremiah after 608 C. (26:1-45:5)

- Jeremiah and the future (30 :1-33:26). These chapters break the biographical narratives which we have been following. However, one important event in Jeremiah’s life is related in chapter 32. It is the account of his buying his cousin’s farm as a sign of his faith in the future, even though it was occupied by the Babylonian army.

These four chapter have been called “the roll of hope” or the “book of comfort.” They probably contain oracles written or spoken on various occasions and which were collected into one scroll and circulated separately for a while. They contain much important material, such as the section on the new covenant (31:31-34). - Jeremiah’s yoke wearing and letter writing (27:1- 29 :32).-These three chapters are a literary unit bound to gether with certain peculiarities of style and a common purpose of counteracting the easy optimism of Judah’s false prophets. In chapters 27 and 28 Jeremiah makes use of the prophetic symbol of the yoke. Chapter 29 contains Jeremiah’s famous letter to the exiles in Babylon advising them to be good citizens of that country since their exile was to last a long

- His Temple sermon and its results (26:1-24).

- Jeremiahs interviews with Zedekiah during the early siege of Jerusalem by Babylon (34:1-22). In verses 1-7 Jeremiah tells Zedekiah of his approaching fate at the hands of the Babylonians, and in verses 8-22 he condemns the king and his nobles for their breach of faith with Hebrew slaves during the siege of Jerusalem.

- Jeremiah’s use of the example of the Rechabites for a lesson in obedience (35:1-19).

- Jeremiah’s book begun (36:1-32).

- A chronological account of the siege and fall of Jerusalem and subsequent events in Jeremiah’s life (37:1-44:30).

- A personal word to Baruch (45:1-5).

IV. Foreign Prophecies (46:1-51:64)

Almost all of the writing prophets of the Old Testament make some references to foreign nations. The books of Amos, Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel contain separate sections devoted to prophecies concerning foreign nations. The presence of such material reveals an awareness and a concern of the prophet with the actions of other nations in relation to his own people and a conviction that God was over the affairs of all men.

The prophecies in this section of Jeremiah are addressed to nine or ten nations of his day announcing the coming judgment of God upon each one. The problems of the date and authorship of this section are very difficult. The Septuagint adds to the difficulty by presenting them in a different place (after 25:13a) and in a different order.

V. An Appendix (52:1-34)[31]See comment on this chapter above, p. 18.

Some High Points

The book of Jeremiah is literally filled with wonderful expressions of faith and words of warning. What constitutes a high point in the book will depend largely upon the under standing and situation of each individual reader. Perhaps the following verses could serve as examples of some high points because of their beauty of expression and depth of insight.

See, I have set you this day over nations

and over kingdoms,

to pluck up and to break down,

to destroy and to overthrow,

to build and to plant

(1:10; cf. 12:16; 18:9; 31:27).

Be appalled, 0 Heavens, at this,

be shocked, be utterly desolate, says the Lord,

for my people have committed two evils:

they have forsaken me,

the fountain of living waters,

and hewed out cisterns for themselves,

broken cisterns, that can hold no water (2:12-13).[32]For an exegesis of this passage see D. David Garland, “Exegesis of Jeremiah 2:10-13,” Southwestern Journal of Theology, II (April, 1960), 27-32. See also V.L. Stanfield, “Preaching Values in Jeremiah,” this issue, pp. 69-80.

For from the least to the greatest of them,

every one is greedy for unjust gain;

and from prophet to priest,

every one deals falsely.

They have healed the wound on my people lightly,

saying, ‘Peace, peace,’ when there is no peace

(6:13-14; 8:10b-11).

Will you steal, murder, commit adultery, swear false ly, burn incense to Baal, and go after other gods that you have not known, and then come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my name, and say, ‘We are delivered!’ only to go on doing all these abominations? (7 :9-10).

I have given heed and listened,

but they have not spoken aright;

no man repents of his wickedness,

saying, ‘What have I done?’

Every one turns to his own course,

like a horse plunging headlong into battle.

Even the stork in the heavens

knows her times;

and the turtledove, swallow, and crane

keep the time of their coming ;

but my people know not

the ordinance of the Lord (8:6-7).

The harvest is past, the summer is ended,

and we are not saved (8:20).

Is there no balm in Gilead?

Is there no physician there? (8:22).

For death has come up into our windows,

it has entered our palaces,

cutting off the children from the streets

and the young men from the squares (9:21).[33]Note that death is pictured as a grim reaper perhaps for the first time in any literature.

Let not the wise man glory in his wisdom, let not the mighty man glory in his might, let not the rich man glory in his riches; but let him who glories glory in this, that he understands and knows me, that I am the Lord who practice kindness, justice, and righteousness in the earth; for in these things I delight, says the Lord. (9:23-24).

Many more favorite and familiar passages from the book of Jeremiah could be added to the above list. But, there are three other passages which present some of Jeremiah’s most unique ideas.[34]See Stanfield, this issue, pp. 70-75.

In many aspects of his thought Jeremiah did not go beyond his predecessors or his contemporaries.[35]Smith, p. 351. As far as we know, Jeremiah had no hope of another life. George Adam Smith says, “Absolutely no breath of this breaks either from his own oracles or from those attributed to him.”[36]Ibid., p. 334. In at least three respects, however, Jeremiah did move beyond his predecessors and his fellows: (1) he saw that sin was a matter of the heart; (2) he was convinced of the complete sovereignty of God and (3) that God would make a new covenant with his people.

1. Sin’s Locus Is in the Heart (17:9)

Jeremiah had much to say about sin, but the most amazing and advanced element in his teaching was that the source of man’s woe was a deceitful and desperately corrupt heart (17:9).[37]Cf. Peake, p. 39. Charles Jefferson said that all thoughtful men agree that there is something wrong with the world – something radically and tremendously wrong. He reviews the many answers which have been given to the question as to the root of the world’s troubles. Some have suggested that matter is the seat of evil. Others have named capitalism, or sectionalism, or socialism, or communism as the root of the world’s troubles. But six centuries before the Christian era a Hebrew prophet said that a sick heart lay at the bottom of man’s wretchedness.[38]Charles E. Jefferson, Cardinal Ideas of Jeremiah (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1928), p. 137. And what is more amazing is that Jeremiah saw the way out. He saw that God could cure a sick heart, or do something even better than that. He can give us a new heart (31:33).

2. The Potter and the Clay (18:1-12)

One of the most familiar illustrations in religious literature is that of the potter and the clay. It is used very sparingly in the Bible (Isa. 29:16; 45:9; 64:8; Rom. 9:21) and twice in the Apocrypha (Wisd. Sol. 15:7; Ecclus. 33 :13). Although the figure did not originate with Jeremiah (cf. Isa. 29:16), it was he who impressed it indelibly on men’s minds.

Jeremiah seems to have learned three abiding lessons from his visit to the potter’s house. (1) He learned that God was sovereign. Just as the clay was in the hands of the potter, so Israel-and as far as that goes, the whole world was in God’s hands. Jeremiah realized that if God was God at all he must be God of all. If God’s sovereignty was limited, then he was less than God.[39]Cf. ibid., p. 91.

(2) A second lesson that Jeremiah learned from the potter was that, although God’s sovereignty is complete, that does not mean that his will is always done, Just as the clay was marred in the hands of the potter, so Israel as God’s vessel had been marred in his hands. God’s sovereignty is complete, but within that sovereignty there is room for man’s choices.

(3) The third lesson which Jeremiah learned from the potter was that of divine patience. When the clay became marred in his hand, the potter did not destroy it nor cast it away, He did not lock up shop and go home. He kept on working. He crushed the clay into submission and “made of it another vessel as it seemed good to him to make it” (18:4).

3. The New Covenant (31:31-34)

The book of Jeremiah reaches its highest peak in this passage. The conception of the new covenant was Jeremiah’s greatest idea.[40]Cf. Jefferson, p. 111, and Peake, p. 43. It is significant that Jeremiah gave us the name of the new Bible six hundred years before it was written. Before Jeremiah could get a vision of the new covenant, however, he first had to realize the breaking up of the old (cf. 11:10; 22:9).

It was not easy for Jeremiah to give up the old. Streane prefaced his commentary with a remarkable quotation from Macaulay:

It is difficult to conceive any situation more painful than that of a great man, condemned to watch the lingering agony of an exhausted country, to tend it during the alternate fits of stupefaction and raving which precede its dissolution, and to see the symptoms of vitality disappear one by one, till nothing is left but coldness, darkness, and corruption.[41]Quoted by G. Campbell Morgan in Studies in the Prophecy of Jeremiah (Westwood, N. J.: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1955), p. 9.

Herein lies the greatness of Jeremiah. A small man can see when it is growing dark, but only a great man can see beyond the darkness to the dawn, Jeremiah saw that the old covenant was abrogated, but God could make another covenant – a covenant written on the fleshly tables of men’s hearts based on forgiveness.

Charles Jefferson concludes his chapter on the new covenant thusly:

Do you observe how high we have come? We are almost up to the level of the New Testament. We are in the vicinity of Jesus. We can overhear Jesus saying, “You must be borne again.” That is an idea of Jeremiah expressed in Jesus’ way. We can overhear Jesus saying, “God is spirit, and they who worship him, must worship him in spirit and in truth.” That is an idea of Jeremiah stated in a phraseology slight ly altered. But there are some things we cannot hear from the mountain top in Jeremiah. We cannot hear Jesus say, ‘This is the cup of the new covenant in my blood.” Jeremiah never foresaw the Mediator of the New Covenant. He saw the New Covenant, but he did not see the Mediator of it. He saw the ideal which was to be worked out in the heart, but he did not know by what means that ideal was to be realized. He did not see Jesus. Nor can we in Jeremiah hear Jesus saying, “In my Father’s house are many mansions. If it were not so I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you. And if I go, I will come again and receive you unto myself.” From the Book of Jeremiah we cannot hear that. The preacher can not find in Jeremiah a text for Easter Sunday. There is no Easter in the calendar of Jeremiah. The idea of immortality never came into any of his sermons, nor so far as we can tell, did that idea ever enter his mind. God spoke to the fathers in the prophets by divers portions and in divers manners, and he has spoken unto us in his Son. Jeremiah saw in part and prophesied in part, but when he who is perfect came, then all that Jeremiah had said was swallowed up in the glory of the final truth. We can go a long way up the mountain side with Jeremiah, but when we reach the highest slopes, we discover that the prophet is no longer by our side. On lifting up our eyes we see no man but Jesus only.[42]Jefferson, pp. 126-27.

References

Southwestern Journal of Theology

To download full issues and find more information on the Southwestern Journal of Theology, go to swbts.edu/journal.